1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

This tough little world traveller has done it all...

|

|

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

|

First published Unique Cars magazine, issue #268, Dec, 2006-Jan, 2007)

1968 London-Sydney Marathon Porsche 911

After rallying the equivalent of more than three times around the planet, this classic 911 is fresh for a new start...

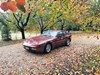

The signature tinny rasp of the boxer six-cylinder engine telegraphs its DNA long before it appears, but what emerges from the cloud of dust looks more like a Moon buggy than the world’s most-beloved sports car.

Covered with a latticework of bars, festooned with air horns and driving lights and with its roof crowned with three jerry cans and four spare wheels and tyres, its arrival creates gasps of incredulity rather than the admiring smiles normally reserved for Stuttgart’s finest.

In 1968, onlookers had to do triple-takes when three similarly decorated Porsches lined up for the start on the inaugural London-Sydney Marathon. Visually, the cars had more in common with the controversial Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, where all the plumbing is on the outside, than any production Porsche.

While the majority of the 98 starters in that milestone event devised by journalist Nick Brittan were equipped to withstand the occasional brush with nature, the factory-prepared Porsches took Teutonic overkill to new heights.

A collision with a tall red kangaroo in a rental car during a pre-event recce in Australia inspired Porsche competition boss Huschke von Hanstein to construct the ultimate roo bar.

Taking full advantage of this external superstructure, Porsche technicians also used it to mount four fully-shod spare wheels and tyres and three 20-litre jerry cans, one of them holding oil and all three plumbed to supply gravity feed to the engine should any of the frontline fuel and lubrication systems be damaged.

Finally, flexible exhaust extensions snaked up from the under-bumper tail pipes of the sports exhaust system, exiting at roof height in case a swollen stream were encountered.

But the sneers turned to cheers some weeks later when two of the three made it home in very respectable positions. Polish rally ace Sobieslav Zasada was on track to finish third, but needlessly waited 30 minutes outside the South Australian control point on the run from Perth to Sydney, unaware of the half-hour time change, while Edgar Herrmann in Car 55 finished 15th and was the first privateer home.

After the event, both Porsches were sold in Australia, ending what for most cars would have been the most dramatic days of their lives, but in the case of the Herrmann car, the London-Sydney Marathon was already just one event in its eventful life and there were many more to come.

Kenyan-based Herrmann, had not heard of the London-Sydney event when he took delivery of the short wheelbase, 1966-build, Polo Red 911T in Stuttgart in early-1967.

His interest was the gruelling East African Safari Rally in 1968, but beforehand, he decided to ‘run-in’ the 911 in a couple of other events. By all accounts, the 911 was nicely broken in by the time it returned to Stuttgart in 1968 for its London-Sydney preparation.

Zasada had convinced the factory to support him in the event by preparing his own 911S and Porsche agreed to carry out similar modifications on the privately-owned cars of Herrmann and Briton Terry Hunter.

The factory work order for the preparation makes fascinating reading and included nearly 40 specialised items including seam-welding the body, strengthening shock absorber mounts, fitting a 200-litre fuel tank to ensure a range of 800km, installing underbody protection and fitting a clutch draining system.

The flat-six 1991cc air-cooled engine, which was normally tuned to 130kW ‘S’ specification for rallies, was given a lower compression ratio and detuned to 120kW to ensure it would run on the poorest-quality fuel, while the five-speed gearbox benefited from a set of close-ratio gears and a limited-slip differential was fitted.

Finally, a large hacksaw, a fierce-looking hand-axe, a two-man wood saw and a two-tonne breaking strain wheel-mounted winch, covered all the other likely eventualities the pioneers should encounter.

You’d think that after all its hard work the 911 would have earned a nice Double Bay garage to rest in after arriving in Sydney, but nothing was further from the truth. Like the legendary French character Papillon going from prison to prison, its torture had only just begun.

The Herrmann car’s new owner, Porsche importer Alan Hamilton, saw in it a ready-made rally machine.

It was converted to RHD and after competing in a series of Victorian Championship events in 1969, lined up for the inaugural Rallycross meeting at Calder in November that year, with its competition including a variety of other rally and ex-London-Sydney Marathon vehicles and a yellow supercharged Torana prepared by Ian Tate for Harry Firth and driven by a certain Peter Brock.

The car’s next big adventure was the 1970 Ampol Round Australia Trial. For this event the car was given a major ‘birthday’ and repainted bright green, however mechanical problems stymied the car’s return to endurance rallying.

Following the Ampol, the 911 was pensioned off and for the next 16 years it was lightly used by several owners before being stored in a neglected state.

Porsche Club member Philip Bernadou saw it in 1986 and was fascinated by its history. He negotiated a purchase price, stripped the car back and then rebuilt it as close to its original factory specification as he could, changing its colour back to what he believed from a code he found on the door jamb, was its original hue.

It was to be an active rally car again, but just as he got it rally-worthy in 1987, the Porsche Cup racing series began. So instead of re-fitting its roo bars and mudflaps, he put on sticky track tyres and sent it around circuits instead, emerging as the winner of Class C in the new series.

After running in several Cup series and a number of Porsche Club events and historic rallies, Bernadou sold the car in tired condition to a South Australian enthusiast. But after being daunted by the restoration project, the car passed through another pair of hands before being acquired two years ago by its present owner, Ian Henderson.

Henderson has a particular penchant for racing Porsches with an Australian history and his garage already houses some magnificent examples: a superb 906 coupe, the 911 2.8 RSR that was once the West Australian sports car champion and the brutish 934 model that won the 1977 and 1980 Australian Sports Car Championship in the hands of Alan Hamilton and Allan Moffat respectively.

However Henderson saw the 911 in a different light to its previous owners – as a genuine, early factory-prepared 911 rally car.

"To me, its importance is being one of these special cars at what was one of Porsche’s most interesting periods," he says. "The London-Sydney Marathon was only a few months of this car’s long and fascinating life, yet because it relates to Australia and it was spectacularly decked out for this event, all the focus has been on it in this role."

So he set out to rebuild the car as it was when Edgar Herrmann drove it from the factory in early-’67.

The starting point was to strip the 911 of all of its post-period features. This meant changing the car back from right to left-hand drive, removing its late-’70s interior, fitting a genuine 911R-type safety cage of the era and removing the later series 2.2-litre engine that had been taken out to 2.5 litres and replacing it with its original 2.0-litre power plant. Thankfully, that engine in un-rebuilt form, came as part of his purchase.

The limited-slip differential was also missing, but thankfully the close-ratio gearbox still remained. Then the work began.

An early discovery during the rebuilding process was that the left-hand front mudguard was different to the right, after a latter-day bruising. Apart from its slightly different shape, it was not seam welded to the central body structure like its neighbour, so that was redressed.

Then came the colour. There is still some disagreement from past owner Bernadou and Henderson on this matter, but the latter is confident from paint samples found in dismantling it that the car was originally painted Polo Red, not Monaco Red as Bernadou believed. So it was rubbed back and repainted.

A period interior with 911R rally seats completed the inside and then it was time for the external ‘roo cage’. The original had long been tossed on the Porsche Cars Australia scrap heap by Alan Hamilton and a replica had been made by Bernadou, so this was powder-coated and re-fitted.

"Of course I wanted to display it as it competed in the London-Sydney event, because we have all its equipment," says Henderson, "but the car should not be overwhelmed by this chapter in its life."

The engine was then rebuilt to original factory 1967 911S specifications and it fired up for the first time in its newly re-born form in mid-2006.

Henderson plans to obtain an Historic Log Book for the car that will allow it to compete as a Group S car in historic racing in Australia. And the car is ideal for historic gravel rallies, or the period categories in tarmac events such as Targa Tasmania and Classic Adelaide.

"I’m tempted to run it in the 2007 Targa Tasmania," he says. "That would be a special 40th anniversary present for the car.I’m sure the late Edgar Herrmann would approve."

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.png)